Supercharging Data through Validation as a Service

The opportunity

Data collected in the process of verifying eligibility for the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP) are handled at multiple levels as they funnel up to the analysts in the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) of USDA. With the goal of improving data quality, and informed by insights from those responsible for data collection at the state level, FNS restructured its approach to data validation, using an API-based validation service. The approach promises to increase data quality and process efficiency without changing how school officials submit their data, and offers an example of validation as a service for other agencies that want to dramatically improve the utility of their own critical data assets.

Background on the program and the data asset

The school meal programs administered by FNS and state agencies provide nutritional, free or low cost meals to over 30 million children each school day. Families can apply for program benefits or may qualify without an application based upon their participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or other programs.

Concept Note: This Proof Point discusses data validation, the process of checking data entries for proper format, reasonable range, and other indicators that make up data quality. This is distinct from program participation verification, which is the process of examining program participants’ information against participation requirements.

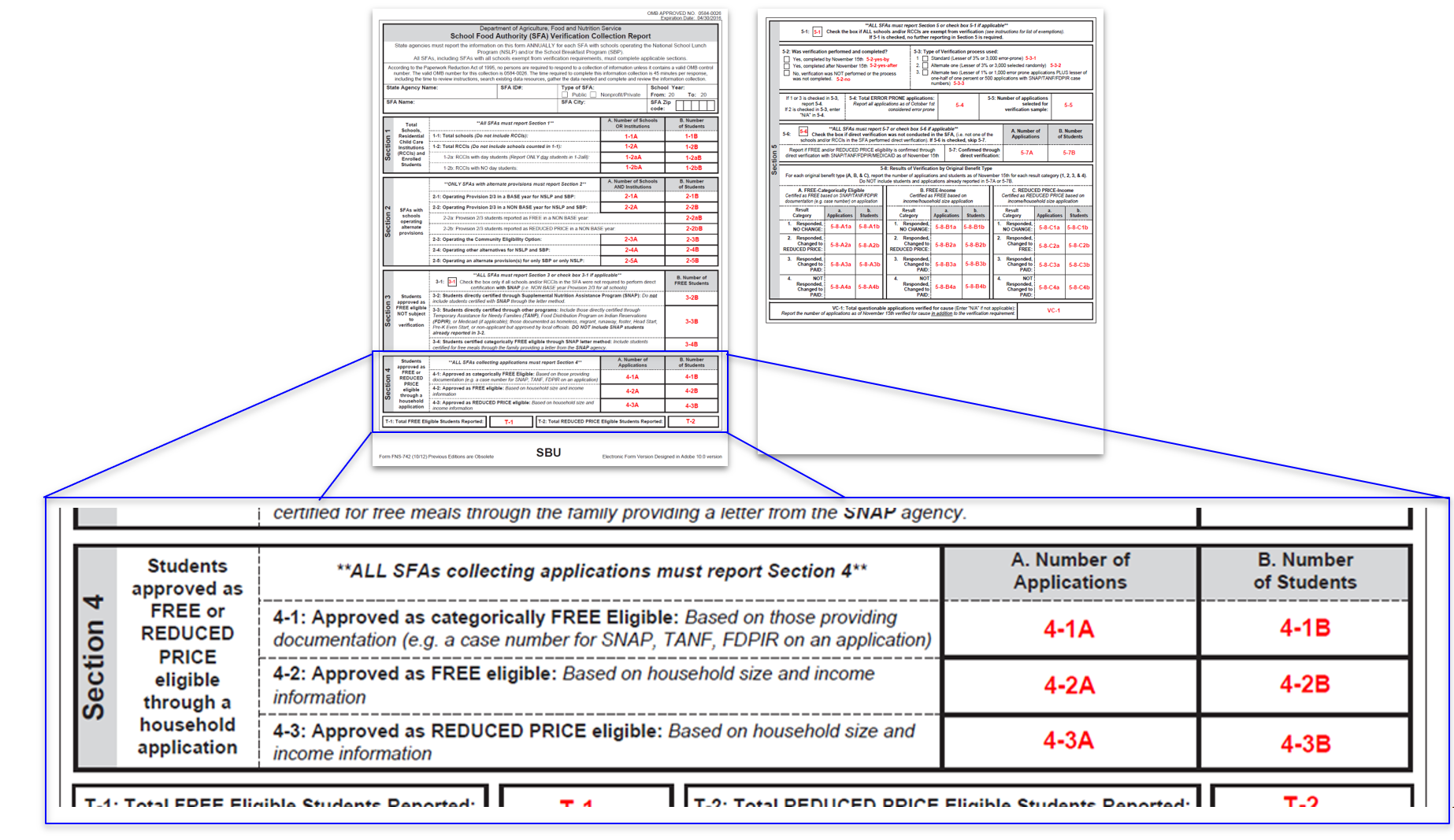

Data collected in the process of administering programs often serve as valuable resources in the analysis that guides policy decisions, informs lawmakers, and fuels important research. The information gathered from thousands of school districts’ Form FNS-742 (School Food Authority (SFA) Verification Collection Report) is especially valuable for analysis, as it is one of the few granular datasets at FNS’ disposal. While other data assets are reported only at the state level, the FNS-742 datasets provide information at the school district level. As a result, FNS-742 data is essential for evidence-based decisions, and ensuring its quality is a high priority.

A data bucket brigade

Each year, school districts verify the eligibility for school meal programs of a sample of their participating households. Personnel enter data from this verification into a form, sometimes still on paper, provided by their state’s administering agency. Each state government collects and aggregates the data from districts, then sends the concatenated data up to the federal level. Sometimes, however, data are not formatted properly, contain obvious or more subtle errors, or are missing required fields. FNS catches many of these errors in a process of automated and manual review that the agency established years ago. The state agency receives immediate system-generated feedback at the point of data submission. FNS follows that up with additional feedback from a manual review of records. The entire data cleaning process, which requires the state to pass error messages back to school districts to remedy and resubmit up the chain, can take several months.

Figure 1. A picture of the paper-based version of the FNS-742 form. Section 4 (shown here) collects the number of students on applications approved for school meal benefits. There are on average 2 students per application reported by school districts, in line with the average number of kids per household in the US. Yet implausibly high student to application ratios are often reported, even as high as 50 in some instances – an obvious error. The additional checks FNS developed attempts to correct this and other errors.

Figure 1. A picture of the paper-based version of the FNS-742 form. Section 4 (shown here) collects the number of students on applications approved for school meal benefits. There are on average 2 students per application reported by school districts, in line with the average number of kids per household in the US. Yet implausibly high student to application ratios are often reported, even as high as 50 in some instances – an obvious error. The additional checks FNS developed attempts to correct this and other errors.

Persistent quality problems

Despite the effort involved in data validation and cleaning, FNS-742 data quality remained a problem, limiting its value as a research dataset. FNS developed a series of new validation checks that promised to greatly improve the quality of the dataset, but the agency was reluctant to increase the burden on an already overtaxed data validation system.

Local validation is a double-edged sword

While FNS was considering ways to improve data quality, states took steps to shorten the data submission-production cycle, adding the traditional FNS data validation rules into their own systems. Now, when district-level personnel provided problematic data, state systems would highlight the errors in near-real time, allowing corrections to be made prior to the data rolling up to FNS.

These steps reduced the time from initial data submission to final data production, but the improved turnaround time alone did not address the need for more rigorous data validation. However, introducing FNS’s new validation checks into 50 separate state systems would generate new inefficiencies and significant new cost for the states. Furthermore, there was a high likelihood that such changes would be implemented unevenly across states, resulting in the need for subsequent work by FNS to untangle the mess.

Researching data quality outliers

The FNS team methodically went through the data and identified several outliers – states with very few errors and states with many errors. Reaching out through regional offices, FNS was able to speak directly to state agencies in each case to review verification and reporting processes. Through this and connections made at school nutrition conferences, FNS staff furthered their understanding of the wide variety of arrangements states have in place to collect and check Form FNS-742 data. They soon realized there was support and enthusiasm at all levels for improved data quality. But they needed an approach that would not impose added cost or burden on state agencies and school districts.

A solution within the existing system

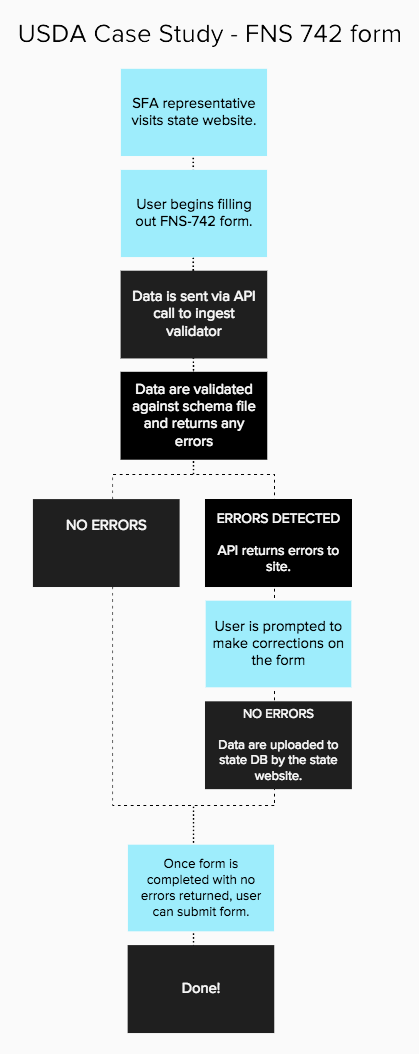

Figure 2. A process flow diagram starting at the point of data entry by a school district into a state system, the system interfacing with the data validation service, and error messages being sent back to the school district official to correct in real time.

Figure 2. A process flow diagram starting at the point of data entry by a school district into a state system, the system interfacing with the data validation service, and error messages being sent back to the school district official to correct in real time.

The FNS team discussed the possibility of implementing a solution at the state level, but without an authoritative, central list of rules, worries about downstream version control would persist. On the other hand, an overly top-down solution might put FNS in the untenable position of dictating to states issues such as which software provider to use in the Form FNS-742 submission process.

FNS asked for help from developers at the General Services Administration (GSA) in operating centralized validation checks as a service. The GSA-based U.S. Data Federation team collaborated with FNS to prototype an API-based data validation service. With FNS serving as a proof of concept, the U.S. Data Federation project was awarded additional 10x program funding to support further development and implementation of the tool.

Together, they built an API accessible over the web. Hooking up to this API, state systems can tap into a far more rigorous and always up-to-date set of checks to highlight erroneous entries to those at the school district level entering the data into the software. States do not need to change vendors, and vendors do not need to update their offerings to keep up with FNS validation changes. Meanwhile, the FNS team can update the central source of validation rules and be confident that these rules will immediately be accessible to the state-level software systems. Perhaps the most attractive aspect of this approach is that none of this restructuring alters the workflow for district-level personnel – there is no learning curve or new training needed.

“We are piggybacking on the process they created, and we can add many more checks than they currently employ without adding burden.”

– Whitney Peters

Next steps

FNS is working with two states to implement the new approach before the fall of 2019, when the process restarts for the school year. The team is encouraged that multiple other states have already reached out to learn how they might adopt this voluntary setup. The U.S. Data Federation team is using its work with FNS to inform other efforts in the vein of data collection up and down the federal-state-local stack.

Postscript

To learn more about the Data Validation Service, contact Ed Harper at Edward.Harper@usda.gov. Ed, the Director of the Office of Program Integrity for the Child Nutrition Programs, along with Program Analysts Janis Johnston and Whitney Peters, conceived of and helped develop the Data Validation Service in collaboration with 18F. You can also check out GSA’s work with FNS on this project at 18F’s blog.